- Last Updated

- February 13, 2022

- 9:24 am

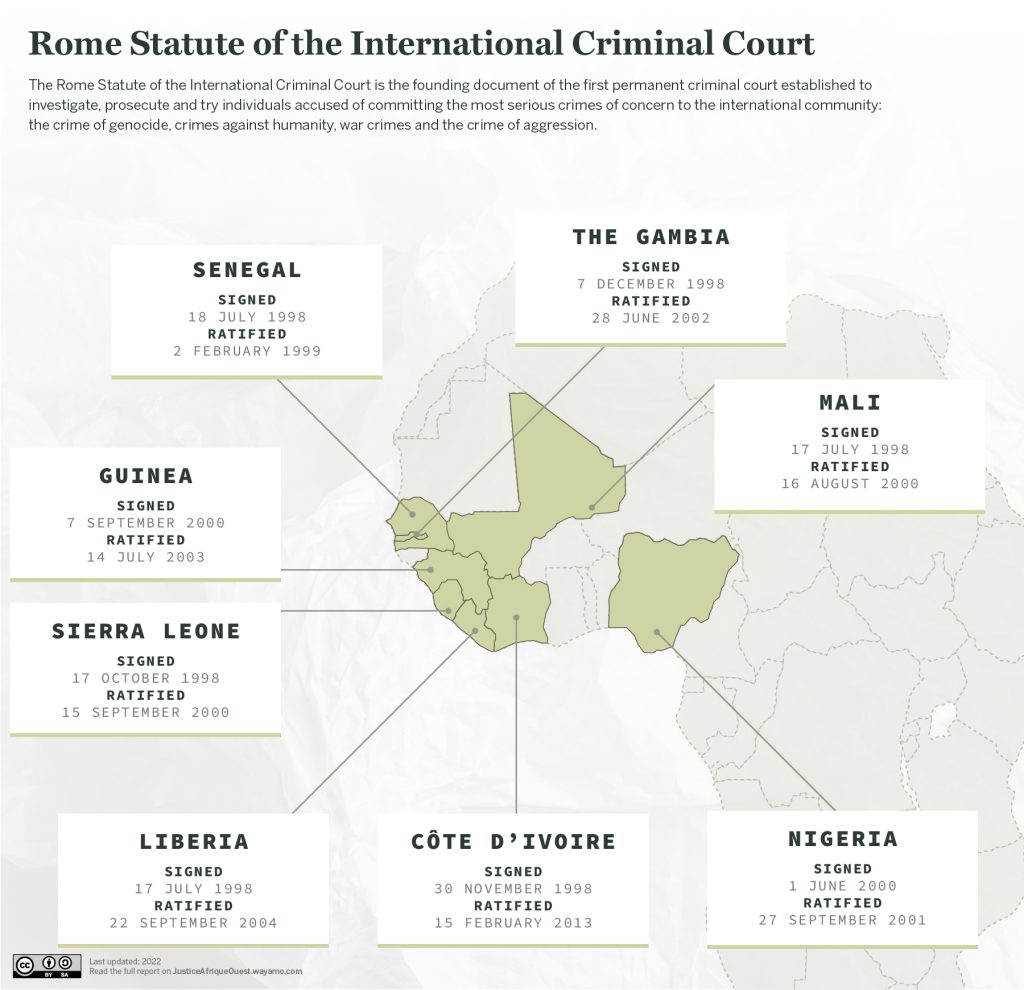

West Africa has long been a strong bastion of support for the ICC”, said Nigerian ICC President Judge, Chile Eboe-Osuji, in a statement. African Union (AU) Members, and notably West African states, were instrumental in the creation of the Rome Statute and the ICC. Indeed, Senegal was the first country in the world to ratify the Rome Statute, and all but two Member States of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) are parties to the Rome Statute. The Court is highly active in the region, with two of the 13 situations under investigation in West Africa (Mali and Côte d’Ivoire), one situation under preliminary examination (Guinea), and the situation in Nigeria where the ICC Prosecutor has concluded its preliminary examination and may now request authorisation from the Judges of the Pre-Trial Chamber of the Court to open investigations.

Although civil society support for the ICC has remained unwavering in the region, West African governments have been vocal in discussions regarding alleged ICC bias against the continent and threats by some AU members of a collective withdrawal from the Rome Statute. Under former President Yahya Jammeh, The Gambia was among the first countries to announce its intention to withdraw but that decision was reversed following the 2017 change of government and the country’s subsequent transition towards democracy.

What is the ICC?

The ICC is the only permanent international tribunal with the jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute individuals charged with the most serious international crimes, namely, genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of aggression. The ICC is a treaty-based court, with its membership comprising those states which have signed and ratified the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. There are currently 123 States Parties to the ICC.

By investigating and prosecuting what have come to be called ‘core international crimes’, the Court endeavours to “put an end to impunity for the perpetrators of the most serious crimes” 1 and in doing so, contribute to the prevention of such crimes being committed in the future. The ICC is a court of last resort, meaning that the Court can only investigate and prosecute international crimes when national jurisdictions are unwilling or unable to do so.2 The role of the ICC is thus to complement, and not replace, the national courts. Civil society, in particular, is proposing to expand the Court’s complementary role in order to reinforce the concept of ‘positive complementarity’, whereby the ICC will actively support efforts by national judiciaries to investigate and prosecute international crimes themselves.3

The Court can open an investigation via three ‘trigger’ mechanisms. Firstly, states can refer situations to the Court, as did Uganda with respect to the conflict in the north of the country, or as did Argentina, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Paraguay and Peru with respect to the situation in Venezuela.4 Secondly, the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) can open an investigation proprio motu (upon its own volition) into situations already under the Court’s jurisdiction. To do so, it must receive authorisation from the Court’s Pre-Trial Chamber: examples of this are the cases of Georgia, Afghanistan and Myanmar/Bangladesh.

Lastly, the United Nations Security Council can refer situations to the ICC, regardless of whether or not the states concerned are parties to the Rome Statute. The Council has so far done so on two occasions, viz., Darfur in 2005 and Libya in 2011: the referral of Syria to the ICC in 2014 failed, due to a veto by Russia and China. Additionally, non-state parties can request that the ICC exercise jurisdiction over alleged crimes on their territory under Article 12(3) of the Rome Statute, as occurred in the case of Ukraine.

The ICC’s temporal jurisdiction extends back to 1 July 2002, the date on which the Court started operating. The Court exercises its jurisdiction over war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide and the crime of aggression when committed either by citizens of a State Party or on State Party territory, or in any case where the UN Security Council refers a situation to the Court, as outlined above.

Play Video

Perspectives from the ICC and Beyond

Fatou Bensouda, former Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), discusses the importance of judicial independence and the rule of law in highly politicised trials. She talks about the challenges she faced as ICC Prosecutor and how she coped with the pressure. She also discusses the impact of the ICC’s jurisprudence on international criminal justice in Africa, the importance of state cooperation, complementarity, and the role of domestic jurisdictions in fighting impunity.

Play Video

International Criminal Justice in West Africa

Roland Adjovi, International Law Advisor for the Global Maritime Crime Programme in West Africa at UNODC, analyses the interplay between national, regional and international judicial mechanisms and their application in West Africa. He also discusses various legal instruments, tools and mechanisms, such as the Malabo Protocol, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the International Criminal Court and hybrid courts.

Citations & References

1: Preamble of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

2: See Article 17 of the Rome Statute.

3: For more on the concept of positive complementarity, see: Emeric Rogier (2018) “The Ethos of ‘Positive Complementarity’” EJIL: Talk! ; Fidelma Donlon, (2011) “Positive complementarity in practice” in Carsten Stahn & Mohamed El Zeidy (eds.), The International Criminal Court and Complementarity: From Theory to Practice, Cambridge University Press, pp. 920-954.

4: So-called ‘state referrals’ have to date been the most common vehicle of activation of the Court’s jurisdiction; other examples are the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali and Central African Republic.

Resources & Commentary

William Shabas An Introduction to the ICC (Cambridge University Press: 2017)

An analysis of the Rome Statute’s substantive law and a guide to relevant ICC procedures, including its operations, jurisdiction, investigative and pre-trial procedure as well as trials, appeals, punishment, the role of victims, and questions relating to the administration of the court. The updated version contains all significant developments in the Court since 2004.

Sang-Hyun Song “The Role of the International Criminal Court in Ending Impunity and Establishing the Rule of Law” (UN Chronicle: 2012)

In this statement, one of the former ICC Presidents revisits the Court’s goals and its role within a global justice system. Song reviews the ICC’s achievements during its first decade of operations, with particular attention to the difficult question of whether the ICC contributes to preventing mass atrocities.

Priorities and Challenges for the ICC in West Africa

Complementarity

How does the ICC interact with domestic accountability efforts in West Africa?

Under the Rome Statute, the ICC can only investigate or prosecute international crimes, if the relevant state in question is unwilling or unable to do so itself. This principle is referred to as ‘complementarity’ and is enshrined in Article 17 of the Rome Statute. The ICC will restrain from investigating or prosecuting international crimes so long as ‘genuine’ domestic criminal justice processes are already taking place at the national level. These must be genuine, as opposed to, say, sham trials that merely endeavour to shield perpetrators from ICC scrutiny. Domestic proceedings must apply to the same persons and substantially the same crimes as those targeted by the ICC.5 This ensures that an accused would, for example, be unable to avoid an ICC indictment for crimes against humanity by standing trial in a national court for a lesser crime, such as corruption.

The Rome Statute leaves room for the exercise of national jurisdiction, not merely out of respect for state sovereignty, but also as a means of supporting the development of international criminal law at the national level. In exercising the complementarity principle, part of the ICC’s role has been to motivate governments to pursue national investigations and prosecutions. This motivation comes in part from the threat of ICC intervention, should states fail to meet their obligation to prosecute international crimes domestically. Beyond that ‘negative’ incentive, the Rome Statute authorises the ICC to provide forms of cooperation relating to national prosecution efforts.6

Jurists and scholars in favour of ‘positive complementarity’ argue that the ICC’s role also includes providing active support to national governments in their efforts to end impunity for the most serious crimes by, for example, sharing expertise, outreach programming, communicating effectively with domestic counterparts, and engaging in training and capacity building exercises. Critics, on the other hand, contend that the ICC should focus its limited resources on the investigation and prosecution in situations which are clearly within its purview, and leave any activities pertaining to the strengthening of national capacity to the Assembly of States Parties, i.e., to state-to-state assistance and cooperation amongst ICC States Parties.

Citations & References

5: See ICC Appeals Chamber at ICC-01/09-01/11-307OA, paras.1,40 (FR) and ICC-01/09-02/11-274OA, paras.1,42. (FR)

6: See the ICC’s state cooperation regime in Part 9 of the Rome Statute.

Resources & Commentary

Rahmat Mohamad “Access to International Justice: The Role of the ICC in Aiding National Prosecutions” (ALCO Journal of International Law: 2012)

An analysis of the Rome Statute’s substantive law and a guide to relevant procedures of the ICC, including its operations, jurisdiction, investigative and pretrial procedure as well as trials, appeals, punishment, the role of victims and questions related to the administration of the court. The updated version accounts for all significant developments in the court since 2004.

Paul Seils “Handbook on Complementarity: An Introduction to the Role of National Courts and the ICC in Prosecuting International Crimes” (International Center for Transitional Justice: 2016)

The Handbook provides a non-technical introduction to the concept of complementarity and what it means for national legal systems. This includes explaining the key questions that guide decisions on the admissibility of an ICC case in contexts where a national case is already under way.

Admissibility

How does the Prosecutor decide, from among many possible cases in her jurisdiction, which to investigate and prosecute?

It is important to separate situation-selection from case-selection. Whereas situations pertain to the territorial contexts under investigation (e.g., the confines of an armed conflict in a region/country), cases pertain to the persons targeted for prosecution by the ICC Prosecutor. The scope of the ICC’s jurisdiction leaves the Prosecutor with the discretion to select, from a wide range of possibilities, which crimes and/or perpetrators to investigate in a given situation and which to prosecute in a potential case against identified individuals (through a warrant of arrest/summons to appear, Article 58 of the Rome Statute).7

Prosecutorial discretion is not absolute. The Rome Statute defines the factors rendering a case ‘admissible’ before the Court.8 Firstly, the ICC’s geographical jurisdiction is not worldwide: it only encompasses the 123 States Parties, the states referred to it by the UN Security Council, and those that have requested that the ICC exercise its jurisdiction on their territory (see above).

Before the Prosecutor can open an investigation, the ‘admissibility’ of the potential case is determined through a preliminary examination. Preliminary examinations assess whether the situation falls within the ICC’s jurisdiction and whether it meets the requirement of complementarity. In assessing complementarity requirements, preliminary examinations are also intended to encourage national governments to open proceedings covering grave crimes committed on their territories or by their citizens, and by doing so, forestall an ICC investigation.

Preliminary examinations proceed in four phases:

Phase 1 – After an initial assessment, does the situation fall within ICC jurisdiction?

The Office of the Prosecutor conducts an initial assessment of information received about alleged crimes (see Rome Statute Article 15 “communications”). Such information can be sent by individuals, groups, states, intergovernmental organisations or NGOs. It can also be referred by the UN Security Council, a State Party, or a non-state party accepting ICC jurisdiction. Situations clearly not under ICC jurisdiction are filtered out at this point.

Phase 2 – Is there sufficient evidence of the crimes?

The Office of the Prosecutor determines whether there is a reasonable basis to believe that the alleged crimes occurred and fall under the jurisdiction of the Court. At this stage, the Prosecutor is only required to have reasonable confidence, based on credible sources, that the alleged crimes actually happened.

Phase 3 – Are those crimes sufficiently grave to fall under the ICC’s ‘subject-matter jurisdiction’ and is the requirement of complementarity met?

During this phase, the Office of the Prosecutor analyses admissibility in terms of gravity and complementarity. The analysis of the alleged crimes will determine whether acts amount to genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, or the crime of aggression and whether they are of sufficient gravity as envisaged by the Rome Statute. Only the gravest of crimes can be prosecuted at the ICC. The requirement of admissibility is met where a State Party is unwilling or unable to genuinely proceed with investigations and prosecutions of the alleged crimes. The Prosecutor will only determine that a domestic case sufficiently ‘mirrors’ the potential ICC case, where the proceedings meet the standard of “substantially the same conduct” committed by the same individual(s) as those under the Court’s scrutiny.

Phase 4 – Would opening an investigation serve the interests of justice and of the victims?

At this stage, the Office of the Prosecutor has already concluded that the case is admissible before the ICC. Phase four determines where a case is in the ‘interests of justice’. There are highly exceptional circumstances in which a case that would otherwise qualify for selection will not be pursued, because to do so would run counter to the aim of preventing serious crimes and ending impunity. There may, for instance, be circumstances where the nature of an ongoing conflict means that the interests of victims would be better served by not pursuing prosecutions. That said, acting in the interest of peace may be relevant too, but it is not equivalent to acting in the interest of justice: the ICC is not, in general terms, constrained by peace and reconciliation considerations.

Further strategic considerations necessarily influence the Prosecutor in exercising his/her discretion. Guided by the ICC’s overarching goals of ending impunity and promoting international law and justice, the Prosecutor will consider the potential impact of an investigation, particularly on victims and their societies.9 Similarly, the Prosecutor must also consider the most efficient use of limited time and resources, something that will have to be weighed against the relative likelihood of an investigation progressing to trial and conviction.

Citations & References

7: See relevant ICC Office of the Prosecutor Policies and Strategies.

8: See Articles 17 and 53 of the Rome Statute.

9: See Article 53 of the Rome Statute.

the Rome Statute.

Resources & Commentary

Bertram Kloss “The exercise of prosecutorial discretion at the ICC: Towards a more Principled Approach” (UTZ: 2017)

The study investigates what guides the Prosecutor in deciding which cases to investigate, as well as the limits of prosecutorial discretion. The report emphasises that this discretion should be exercised with the aim of contributing to the ICC’s overall purpose: promoting standards of international law and their application

International Criminal Court Office of the Prosecutor “Policy Paper on the Interests of Justice” (September 2007)

This policy paper from the OTP sets out the Office’s interpretation of the Rome Statute provision allowing for exceptional circumstances in which a case that otherwise would qualify for selection is not pursued, based on the “interest of justice”.

Anni Pues “Prosecutorial Discretion at the International Criminal Court” (Hart Publishing: September 2020)

This book details each stage of the ICC Prosecutor’s decision-making process when assessing the admissibility of a possible investigation.

Impact and efficacy of the ICC

Has the Court lived up to expectations in the years since its formation?

The answer to this question depends, invariably, on what one’s expectations of the ICC are. For some, the ICC, as a permanent international tribunal, is unique in its ability to fill an impunity gap for the most serious crimes and has done important work in advancing justice for some of the worst atrocities of the 21st century. Other legal experts and activist groups contend that the Court has fallen short of its potential during its almost two decades of operations. Underlying this criticism is the open question of how to measure the ICC’s impact and efficacy:

- Is it a mere matter of the number of arrest warrants, indictments, prosecutions or fair trials?

- Is success better measured by the Court’s ability to motivate States to open national proceedings, to engender peace and reconciliation or foster respect for human rights and dignity?

- Is the potential to prevent mass atrocity a better measure of success and, if so, can the counterfactual impact of crimes not committed be measured?

- How do reparations afforded through the Court’s legal framework play into this?10

In recent years, both critics and friends of the Court have expressed the concern that the ICC has not achieved a standard of prompt, competent and economical delivery of justice.11 With eight convictions in more than ten years, at a cost of nearly one billion dollars, the Court has proved to be a slow and, to many critics, an expensive path to justice. In the handful of cases that did progress to trial, the Court has performed less effectively than many had hoped, with proceedings marred by poor judicial decisions, staffing controversies, inadequate case construction and investigation, and an overly ambitious docket given the size of its staff.12 In light of these concerns, an Independent Expert Review of the Court was conducted at the request of the Assembly of States Parties. Submitted in September 2020, the report details the Court’s internal problems, and recommends extensive reforms to its governance structure and work culture.13

While many of these criticisms are pertinent, one should nevertheless bear in mind the unique and significant challenges facing the Court. Expectations of the Court are high and, in some cases, possibly unrealistic. The Court has not received sufficient diplomatic or financial support to pursue its mandate effectively, and has acknowledged that its work is limited by the support it receives.14 Moreover, as a court of last resort, the ICC was never intended to shoulder the full burden of holding those most responsible for international crime to account.

The Court’s size and structure allow it to manage, at most, two or three cases a year.15 These cases take much longer to investigate and bring to trial when the States Parties involved are unwilling to cooperate with proceedings. The Court is further limited by its geographical jurisdiction, the range of crimes it can investigate, and how far back in time it can probe. Given these restrictions, depending on the ICC to bring the world’s most serious criminals to justice would, as Lisa Laplante has put it, “be a gift to impunity.” 16

In light of the above, it would be useful for the ICC to engage in better expectation management, communicating a more sober vision of what is achievable, rather than promising victims and the international community that it can achieve justice, peace, reconciliation, and global political change through a handful of sporadic prosecutions. Needless to say, this is also a responsibility of civil society and state. In particular, the Assembly of States Parties and its members have a central role to play in encouraging cooperation, positive complementarity, and collaboration between like-minded institutions engaged in addressing international crimes, such as the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism for Syria and the Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar.

Citations & References

10: For some analysis, see Philipp Ambach (2020), “Punitive to Restorative Justice: Victims’ Participation, Reparations and Theories of Punishment”, in Why Punish Perpetrators of Mass Atrocities? by Florian Jeßberger & Julia Geneuss (eds.), Cambridge University Press, pp.364-379.

11: Guénaël Mettraux et al. (2014) “Expert Initiative on Promoting Effectiveness at the International Criminal Court”

12: Richard Dicker (2020) “Time to Step up at the ICC”, HRW.

13: Douglas Guilfoyl (2020) “The International Criminal Court Independent Expert Review: questions of accountability and culture”, EJIL: Talk!

14: Raad Al Hussein et al. (2019) “The International Criminal Court Needs Fixing“, Atlantic Council.

15: Lisa Laplante (2010) “The Domestication of International Criminal Law: Proposal for expanding the International Criminal Court’s Sphere of Influence“, John Marshall Law Review.

16: Ibid.

Resources & Commentary

Raad Al Hussein et al., The International Criminal Court Needs Fixing (Atlantic Council: 2019)

Four former presidents of the International Criminal Court’s Assembly of States Parties, the Court’s management oversight and legislative body, argue that victims around the world look to the Court as their best, and often only, hope for accountability. But the Court’s central purpose is too often not matched by its performance as a judicial institution. They argued that an independent assessment was needed to understand and address concerns about the quality of proceedings and management. For their part, States Parties need to increase their support of the ICC.

Independent Expert Review of the International Criminal Court

and the Rome Statute System Final Report (September 2020) (FR)

This is the final report of a team of independent experts tasked with making practicable recommendations on ways to strengthen the ICC and improve its performance and efficiency. The report contains 384 recommendations of varying complexity and urgency. Amongst the priorities identified, the report recommends that the organs of the Court work to increase unity of purpose, better delegate duties, and reduce redundancies. The experts also make suggestions for improving the regulatory framework and measuring the Court’s performance.

Lisa J. Laplante “The Domestication of International Criminal Law: Proposal for expanding the International Criminal Court’s Sphere of Influence” (John Marshall Law Review: 2010)

The article proposes measuring the success of the ICC through the lens of complementarity. Do ICC engagements advance the goal of aligning domestic judicial proceedings with international standards? This extends to the impact of the ICC on transitional justice, as a broader vision of promoting accountability and judicial reform at the national level.

Guénaël Mettraux et al. “Expert Initiative on Promoting Effectiveness at the International Criminal Court” (2014)

The report is drawn up by an independent group of international law practitioners and professors, all of whom practised in international criminal tribunals and domestic jurisdictions. The report finds that the ICC has performed less effectively than it should. The experts’ report identifies and offers realistic solutions to effectiveness challenges across a broad range of concerns (i.e., investigations, evidence, victims’ participation, witness protection, etc.).

The ICC in Africa

What motivates the debate about the overrepresentation of Africans before the ICC?

The Following the African Union State Party Assembly in January 2017, the AU resolved to collectively withdraw from the ICC. The statement was the culmination of long growing discontent among some influential leaders on the continent, who insisted that the ICC was biased and had unevenly focused on Africa and its leaders. Concerns had likewise been raised by victim communities that the ICC’s investigations had run roughshod over and disregarded sensitive political contexts and fragile peace processes.

Some concerns are self-serving. African civil society groups have accused their representatives at the AU of instrumentalising the perception of an ICC bias against Africans, as an effort to protect themselves from accountability.17 Almost twenty years after the ICC became a functioning tribunal, not a single non-African has been publicly targeted by an arrest warrant. Whether rhetoric or reality, perceptions that the ICC is biased against weaker states have hobbled the Court’s credibility.

The threat of a collective withdrawal blandished by influential cadres of the AU has generated worldwide concern about the legitimacy and longevity of the Court. In 2015, South Africa, The Gambia, and Burundi all initiated proceedings to withdraw from the ICC, though Burundi — where an active ICC investigation is presently under way — was the only state to follow through. African civil society maintains that continent-wide support for rejecting the Court is not as strong as AU statements would have people believe, and other African states have been vocal in their support for the Court.

African states and civil society groups have shown strong backing for the ICC since the Court’s inception, and the AU’s published Withdrawal Strategy does not represent the unanimous position of its members: indeed some, such as Nigeria, Cape Verde and Senegal, have adopted a firm stance against withdrawal. There are also practical considerations that make a collective withdrawal unlikely.

The AU Withdrawal Strategy is non-binding and has no legal impact, given that a collective withdrawal is not a legal option for States Parties to the Rome Statute (inasmuch as Article 127 requires an individual declaration of withdrawal).18 In like manner, many states do not accept that it is for the AU to take decisions which properly fall within the remit of sovereign states. Moreover, with the collapse of the ICC’s cases against Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta and Deputy President William Ruto, former Sudanese President al Bashir’s ouster, and former South African President Jacob Zuma’s fall from power, political interest in anti-ICC positions has waned.

Citations & References

17: Sarah Kasande, Chris Gitari and Mohamed Suma (2017) “AU Strategy for Collective Withdrawal from ICC a Non-Starter”, International Center for Transitional Justice.

18: See Article 127 of the Rome Statute. Though entitled ‘draft’, this document is the final version of the statement of collective withdrawal from the ICC released by the AU.

Resources & Commentary

Charles Chernor Jalloh “Regionalizing International Criminal Law?” (International Criminal Law Review: 2009)

The article maintains that it is not in Africa’s best interest to ostracise the ICC, emphasizing the benefits of complementarity in establishing national level measures for the prevention and punishment of international crimes. Jalloh equally argues that the Court, and especially the Office of the Prosecutor, must take the AU’s criticisms more seriously, noting the legitimacy of the Court itself is at stake, should it fail to do so.

Assembly of the African Union Draft, Decisions, Declarations, Resolutions and Motion (Twenty-eighth Ordinary Session, 30-31 January 2017)

Though entitled ‘draft’, this document is the final version of the statement of collective withdrawal from the ICC released by the AU. The declaration is directed at the UN SC, urging the body to withdraw the arrest warrant against President Al Bashir of Sudan.

Lisa Sarah Kasande, Chris Gitari and Mohamed Suma “AU Strategy for Collective Withdrawal from ICC a Non-Starter” (International Center for Transitional Justice: 2017)

The AU resolution to collectively withdraw is premised on the contention that the ICC is biased and has unevenly focused on Africa and its leaders. From the perspective of civil society, the proposed collective withdrawal is an attempt by some influential African leaders to instrumentalise media portrayals of the court as neo-colonial, in order to protect themselves from accountability.

Mark Kersten “Building Bridges and Reaching Compromise – Constructive Engagement in the Africa ICC Relations” (Wayamo Foundation: 2018)

This report outlines and addresses the primary concerns that African states and communities have raised with respect to the ICC. It offers insights into how the relationship can be improved and strengthened going forward, and calls for ongoing engagement between African actors and the Court.