Hissène Habré is President of Chad

Habré’s one-party state was characterised by widespread human rights violations and acts of ethnic cleansing. The longevity of his rule was due in part to support from France and the United States.

Habré is deposed and flees to Senegal

After a rebel offensive led by Idriss Déby, Habré fled to Cameroon, and the rebels entered N'Djamena on 2 December 1990. Habré subsequently went into exile in Senegal.

Idriss Déby assumes office of the President of Chad

Déby won elections in 1996 and 2001. After term limits were eliminated, he won again in 2006, 2011, and 2016.

Chadian victims file criminal complaint against Hissène Habré in Senegal

The complaint asserted that Senegal had jurisdiction to bring Habré to trial based on the 1984 UN Convention against Torture, ratified by Senegal. The Convention obliges states to either prosecute or extradite alleged torturers who enter their territory.

- Document: 1984 UN Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

Habré arrested in Senegal for the first time

Habré is placed under house arrest and a Senegalese court charges him with torture and crimes against humanity.

Abdoulaye Wade elected President of Senegal

The new president publicly states that Habré would not be tried in Senegal.

Investigations in Senegal halted

The magistrate who had indicted Habré and was pursuing the pretrial investigation was transferred from his post.

Dakar Court of Appeals dismisses charges

The court rules that Senegal had no competence to pursue acts of torture that were committed outside the country.

- Document: Hissène Habré case, Dakar Court of Appeal, 4 July 2000: "the Senegalese courts cannot take cognizance of acts of torture committed by a foreigner outside the Senegalese territory regardless nationalities of the victims. The wording of Article 669 of the Criminal Procedure Code excludes the jurisdiction of the Senegalese Courts”

Human Rights Watch discovers Documentation and Security Directorate (DDS) files

HRW discovers files from Chad’s Habré-era secret police known as the DDS. The files contain tens of thousands of documents, including daily prisoners lists and details of deaths in detention, interrogation reports, surveillance reports, and death certificates. Most significantly, the files detail Habré’s direct authority over the DDS and personal involvement in hundreds of the crimes documented, including 1,265 direct communications from Habré to the DDS about 898 different detainees. In total, the files named 12,321 victims of abuse, 1,208 of whom died in detention.

Court of Cassation Rules Senegal lacks jurisdiction

Senegal's highest court (Cour de cassation) upheld the decision of the Dakar Court of Appeal barring criminal proceedings against Habré. The decision was based on the absence of legislation establishing jurisdiction to prosecute foreign residents who had allegedly committed acts of torture outside Senegal.

Complaint to the UN Committee against Torture (CAT)

A coalition of Chadian victims lodged a complaint against Senegal with the UN Committee against Torture (CAT).

CAT intervenes in Habré expulsion from Senegal

CAT intervenes in Habré expulsion from Senegal

President Wade declares publicly that Habré has one month to leave Senegal. In a preliminary ruling, CAT calls on Senegal to “take all necessary measures to prevent Hissène Habré from leaving the territory of Senegal except pursuant to an extradition demand”.

International Jurisdiction case filed in Belgium

A group of Hissène Habré’s victims files a case against him as a step towards his extradition. Belgian law expressly included the principle of universal jurisdiction, meaning Habré could be tried for international crimes within its territory (the law was repealed in 2003, by which time the case had already moved to Senegal).

Chad waves Habré’s Head of State Immunity

Chad’s justice minister, Djimnain Koudj-Gaou, writes to Judge Fransen of Belgium confirming that Chad would waive any immunity that Habré might seek to assert.

Belgium requests extradition

Belgian Judge Fransen issues an international arrest warrant against Hissène Habré. The same day Belgium asks for Habré’s extradition from Senegal.

Habré arrested in Senegal for the second time

Senegalese authorities arrest Hissène Habré.

Indicting Chamber rules “No Jurisdiction” on extradition

The Indicting Chamber of the Court of Appeals of Dakar rules that it lacks jurisdiction to rule on an extradition request against a former head of state. Under Senegalese law, the decision thus went directly to President Wade.

Habré placed at “Disposition” of the African Union

The day after the court decision, the interior minister of Senegal issued an order placing Hissène Habré “at the disposition of the President of the African Union.” Stating that after forty-eight hours Hissène Habré would be expelled to Nigeria. The foreign minister of Senegal, Cheikh Tidiane Gadio, announced in a communiqué that: The State of Senegal would “abstain from any act which could permit Hissène Habré to not face justice” and considered “it is up to the African Union summit to indicate the jurisdiction which is competent to try this matter”.

African Union sets up Committee of Eminent African Jurists (CEAJ)

The CEAJ is established to consider the options available for Hissène Habré’s trial. Their priority considerations are ensuring, “fair trial standards,” “efficiency in terms of cost and time of trial,” “accessibility to the trial by alleged victims as well as witnesses,” and “priority for an African mechanism”. Ultimately the CEAJ rules that, as a State party to the Convention Against Torture, “Senegal is under an obligation to comply with all its provisions.” Citing the CAT ruling, it added that “[i]t is therefore incumbent on Senegal in accordance with its international obligations, to take steps, not only to adapt its legislation, but also to bring Habré to trial.”

CAT ruling calls for Habré to be extradited or prosecuted

The Committee against Torture ruled that Senegal violated UN CAT and determined that Habré must either be prosecuted in Senegal or extradited to a country where he would face trial. The Committee also noted Senegal’s obligation to “adopt the necessary measures, including legislative measures, to establish its jurisdiction” over Hissène Habré’s alleged crimes.

African Union calls on Senegal to prosecute Habré “on behalf of Africa”

President Wade declares Senegal’s accession to the request.

- Document: African Union decision that Habré be tried in Senegal

Senegal commits to revising its laws

Senegalese government spokesman El Hadji Amadou Sall says that Senegal would establish a governmental commission under the Minister of Justice to oversee the legal changes, make contact with Chad, create a witness protection program, and raise money to carry out the investigation and trial.

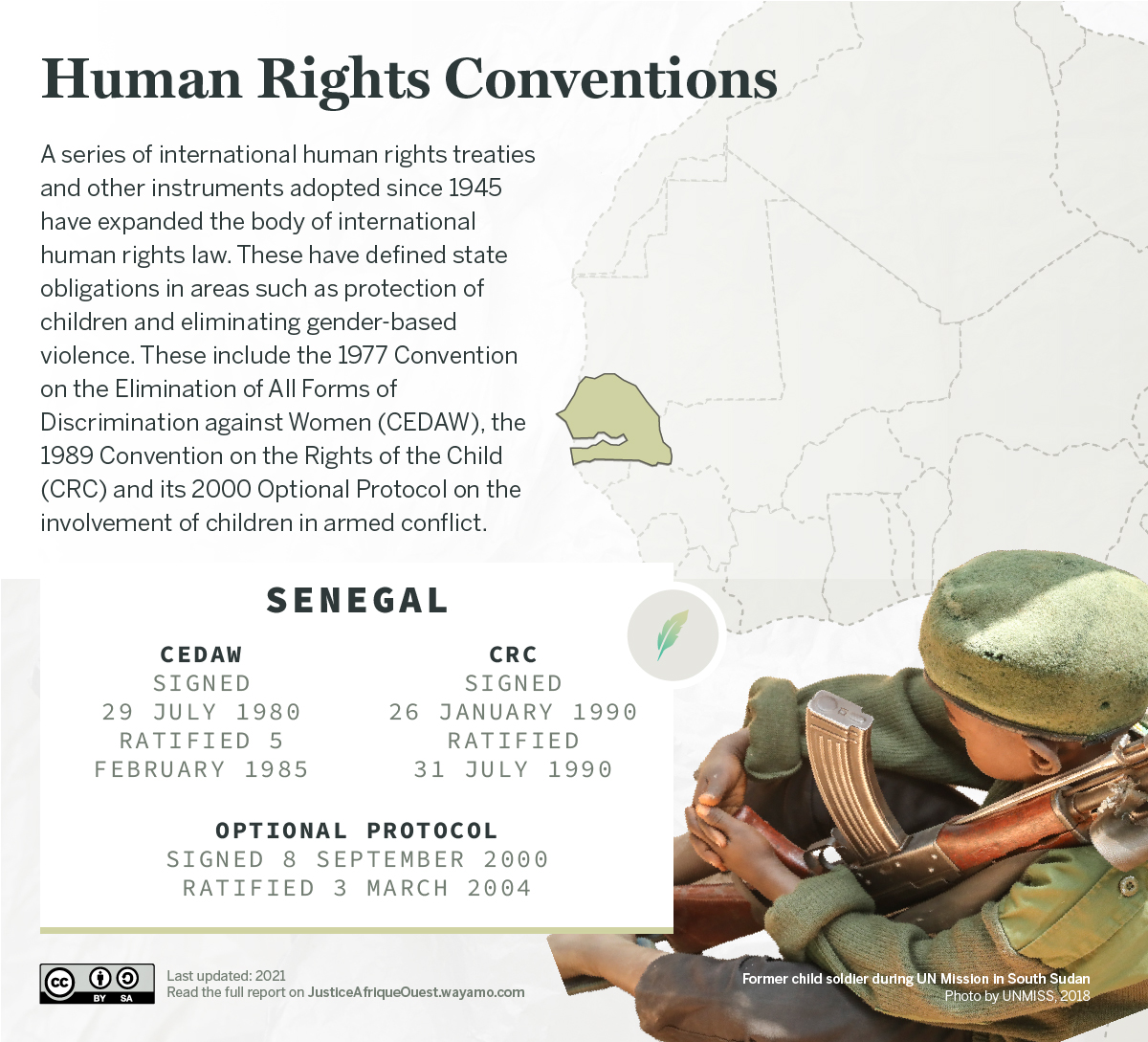

Senegal passes law allowing trial of Rome Statute Core Crimes

The President of Senegal promulgated the Law No. 2007-05 amending the Code of Criminal Procedure relating to the implementation of the Rome Statute. Law No. 2007-05 allows for the trial of suspects based on the principle of universal jurisdiction and provides that offences codified in the Rome Statute would not be subject to any statute of limitations.

Chad court sentences Habré to death in absentia

Habré is condemned to death along with 12 others for planning to overthrow the government after a trial in N'Djamena.

Habré files case at ECOWAS Court challenging Senegal's jurisdiction

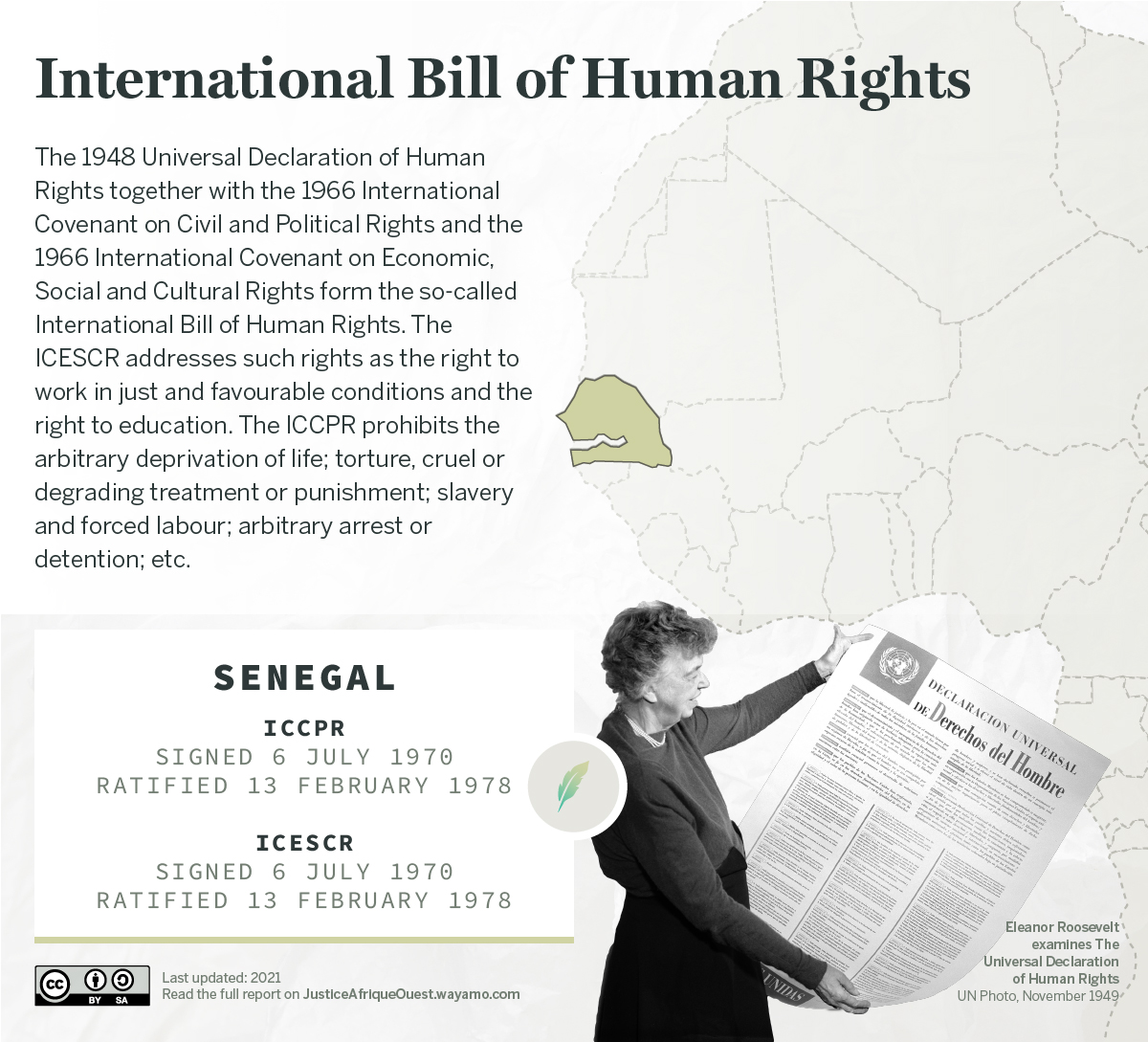

Habré files a case arguing that Senegal passed the laws necessary to assert jurisdiction over his alleged international crimes only after he committed them, violating his right under Article 15 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) to not be retroactively prosecuted.

ECOWAS Court rules in Habré favour

The ECOWAS Court partially grants Habré’s application, finding Senegal would violate the prohibition against adopting retroactive criminal legislation should Habré stand trial for international crimes committed abroad in its domestic courts. ECOWAS thus determined that Senegal could only try Habré before a judicial body with an international character.

- Document: Hissene Habré v Republique du Senegal, judgment of18 November 2010, No. ECW/CCJ/JUD/06/10

International Court of Justice (ICJ) decides that Senegal must prosecute or extradite Habré

The ICJ rules on the Belgian application instituting proceedings against Senegal regarding the application of CAT provisions requiring state parties to prosecute or extradite alleged torturers. The ICJ judges hold that if Senegal did not try the alleged torturer or extradite him to Belgium, it could be held responsible for a breach of its obligations, pursuant to Article 7(1) of the Convention against Torture.

- Document: Questions relating to the Obligation to Prosecute or Extradite (Belgium v. Senegal), judgment of 20 July 2012, (www.icj-cij.org)

President Macky Sall takes office in Senegal

Senegal and the African Union agree to establish Extraordinary African Chambers (EAC)

The ad hoc tribunal is established with jurisdiction to try Hissene Habré. The EAC Statute is integrated into the agreement. The agreement incorporates the EAC into Senegal’s judicial system and vests it with jurisdiction over the international crimes committed in Chad for the period in which Habré was in power (7 June 1982 until 1 December 1990).

Senegalese Parliament authorises ratification of the Senegal-AU agreement

Chad and Senegal agree to grant EAC jurisdiction in Chad

The agreement grants the EAC jurisdiction to conduct investigations in Chad, as if it were Senegal. The agreement includes the right to travel throughout the country, question witnesses and visit former prisons.

Habré arrested in Senegal for the third time

Habré was arrested in Dakar and placed in police custody.

Habré charged with crimes against humanity, war crimes and torture, and placed in pretrial detention.

Twenty top security agents from Habré regime convicted in Chad

A Chadian criminal court convicts 20 Habré-era security agents on charges of murder, torture, kidnapping, and arbitrary detention. The court also awards 75 billion CFA francs (approximately USD 140 million) in reparations to 7,000 victims, ordering the government to pay half and the convicted agents the other half.

Habré convicted by the Extraordinary African Chambers

Habré is convicted of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and torture, including sexual violence and rape, and sentenced to life in prison.

Appeals Court confirms conviction and opens African Union Trust Fund for Victims

Habré victims seek reparations at African Commission on Human and People’s Rights

Seven thousand victims of the Habré regime file a human rights complaint against the Government of Chad before the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. The complaint accuses Chad of failing to comply with a judgement of the Special Criminal Court of N’Djamena of 25 March 2015. The Court awarded approximately USD 125 million in compensation to 7,000 victims who participated in the proceedings as civil parties.

Victims await reparations

Chad's government is yet to provide reparations ordered by its court in 2015 to 7,000 victims of grave crimes under Habré’s rule.