- Last Updated

- February 14, 2022

- 4:58 pm

Given how widespread the commission of international crimes remains, ending impunity for such atrocities will only be possible if domestic actors assume the brunt of the work of holding perpetrators to account, thus addressing the needs of victims and survivors, and establishing respect for human rights and dignity.

Domestic accountability is not without challenges. Grave and widespread atrocities most often occur in contexts of violent conflict or political repression, where a tumultuous climate and institutional weaknesses undermine law, safety and accountability efforts. Even in contexts with judicial capacity and political will, many domestic courts face legal barriers to prosecuting international crimes. Before these offences can be prosecuted at the national level, legislatures may need to amend existing laws or draft new ones that bring international crimes into domestic legislation.

International or hybrid criminal courts may be the best option where national courts lack the capacity or legal framework to hold genuine domestic criminal proceedings against individuals, or in contexts where the security or political situation renders domestic trials non-viable or impossible.

In many cases, strengthening national judicial institutions remains the best hope for victims and communities most affected by international crimes to see justice one day. Given the vast number of potential cases, as well as the high financial and time investment needed to create and maintain international and hybrid tribunals, most victims of international crimes will never find redress and repair without domestic courts assuming a central role in justice-seeking. What is more, domestic trials offer victims and societies proximity to proceedings, thereby bringing opportunities for direct engagement with justice-seeking initiatives. Strengthening national criminal justice institutions also has a potential preventative effect, reducing the possibility of re-occurrence of grave crimes by breaking a culture of impunity and rebuilding trust in the judiciary.

Play Video

International Criminal Justice in West Africa

Roland Adjovi, International Law Advisor for the Global Maritime Crime Programme in West Africa at UNODC, analyses the interplay between national, regional and international judicial mechanisms and their application in West Africa. He also discusses various legal instruments, tools and mechanisms, such as the Malabo Protocol, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the International Criminal Court and hybrid courts.

Resources & Commentary

Clair Duffy and Eric Witte “Options for Justice: A Handbook for Designing Accountability Mechanisms for Grave Crimes” (Open Society Justice Initiative: 2018) (FR)

The design of accountability mechanisms for grave crimes has a significant influence on their efficacy and impact. Recognising this, the Handbook seeks to inform the design of new institutions by offering lessons from experiences gained in designing justice models over the past 25 years. It is a guide to policymakers to help navigate costs, benefits and even contradictions in design choices for accountability mechanisms.

Eric Witte “International Crimes, Local Justice: A Handbook for Rule of Law Policymakers, Donors and Implementers” (Open Society Justice Initiative: 2011) (FR)

Securing justice for a larger number of victims of international crimes depends on national jurisdictions being willing and able to take on the task. This Handbook offers a guide to members of the international community committed to supporting states that are seeking local justice for international crimes. It covers policy questions as well as technical issues, addressing the main areas where states require assistance in meeting international standards for the due process of law.

Alejandro Chehtman and Ruth MacKenzie Capacity Development in International Criminal Justice: A Mapping Exercise of Existing Practice with Annex (DOMAC: September 2009)

This project involves a mapping exercise of capacity-development initiatives implemented to support justice for international crimes, with the goal of developing an analytical framework for assisting the impact of such initiatives. The exercise finds that capacity development should be understood as a multi-level problem, involving individual, institutional and contextual aspects. Many of the successes and shortcomings of the initiatives reviewed are understood by looking at the synergies between these levels of engagement.

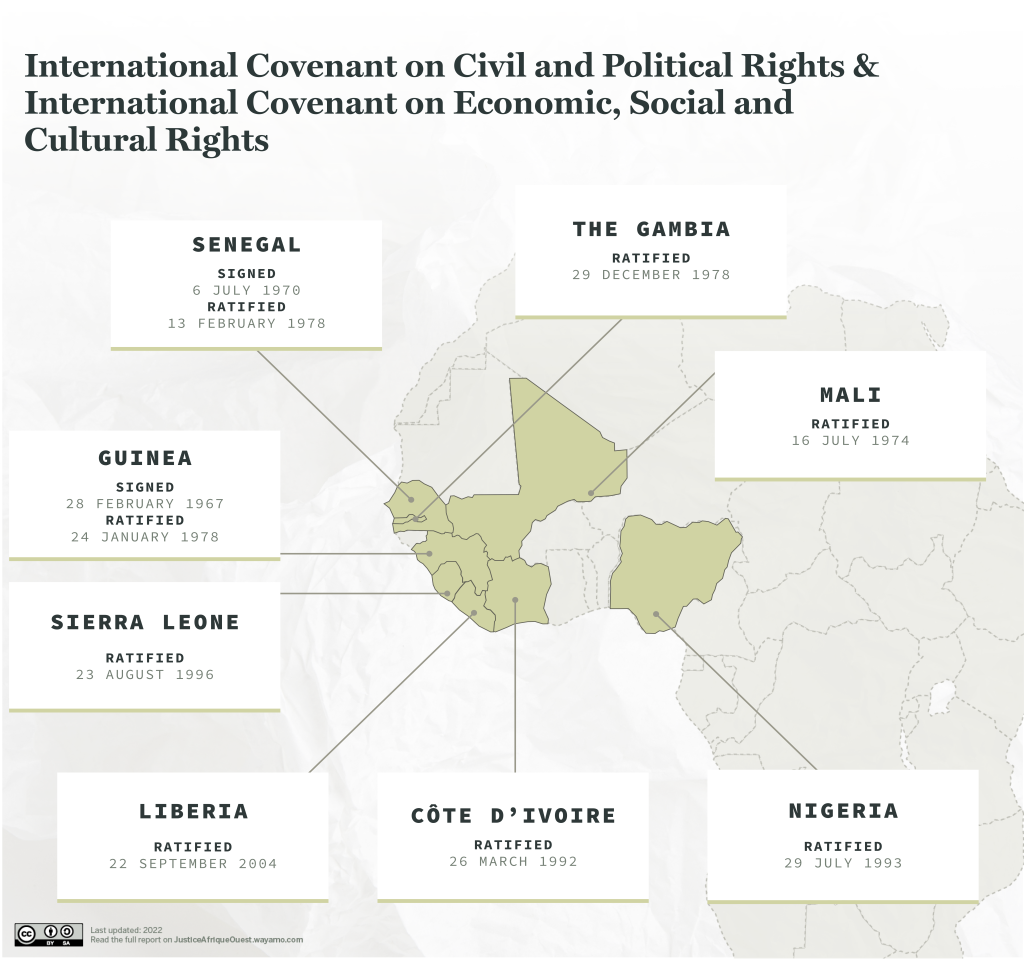

Legislation and Treaties

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and its first Optional Protocol

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

- International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

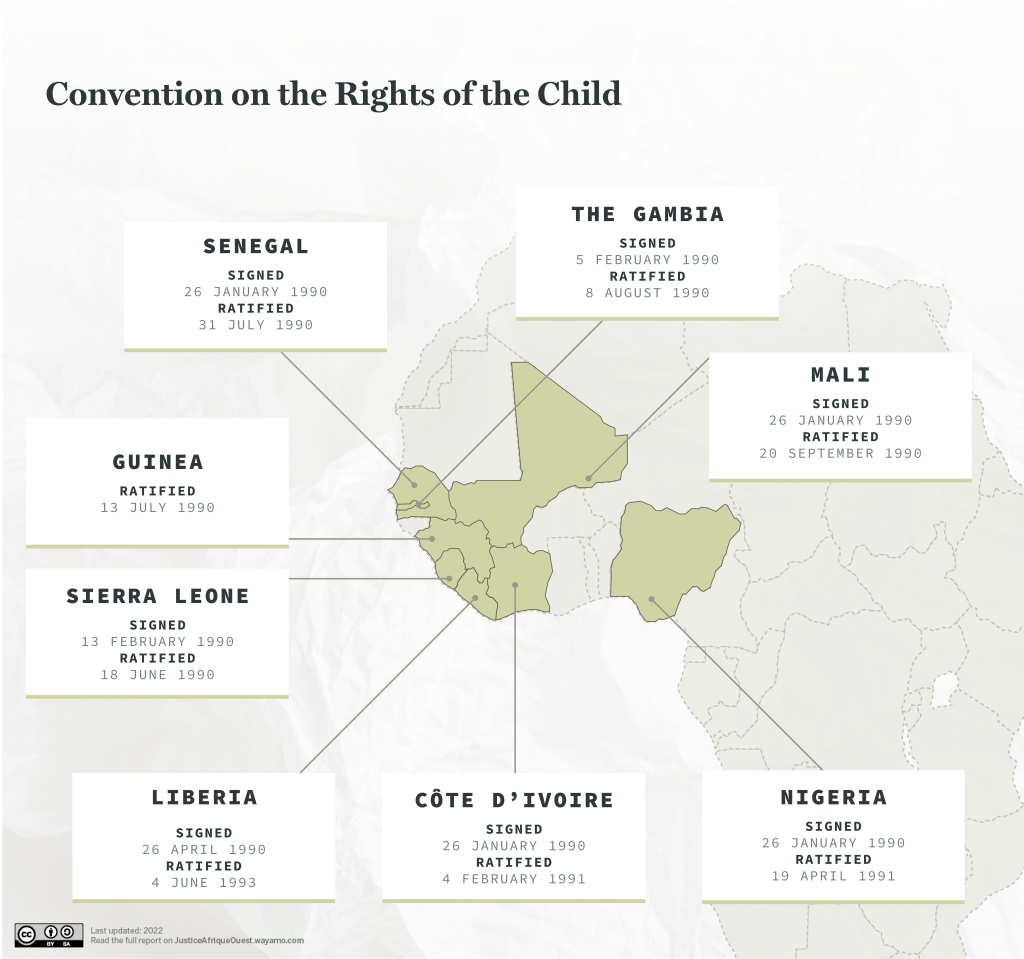

- Convention on the Rights of the Child

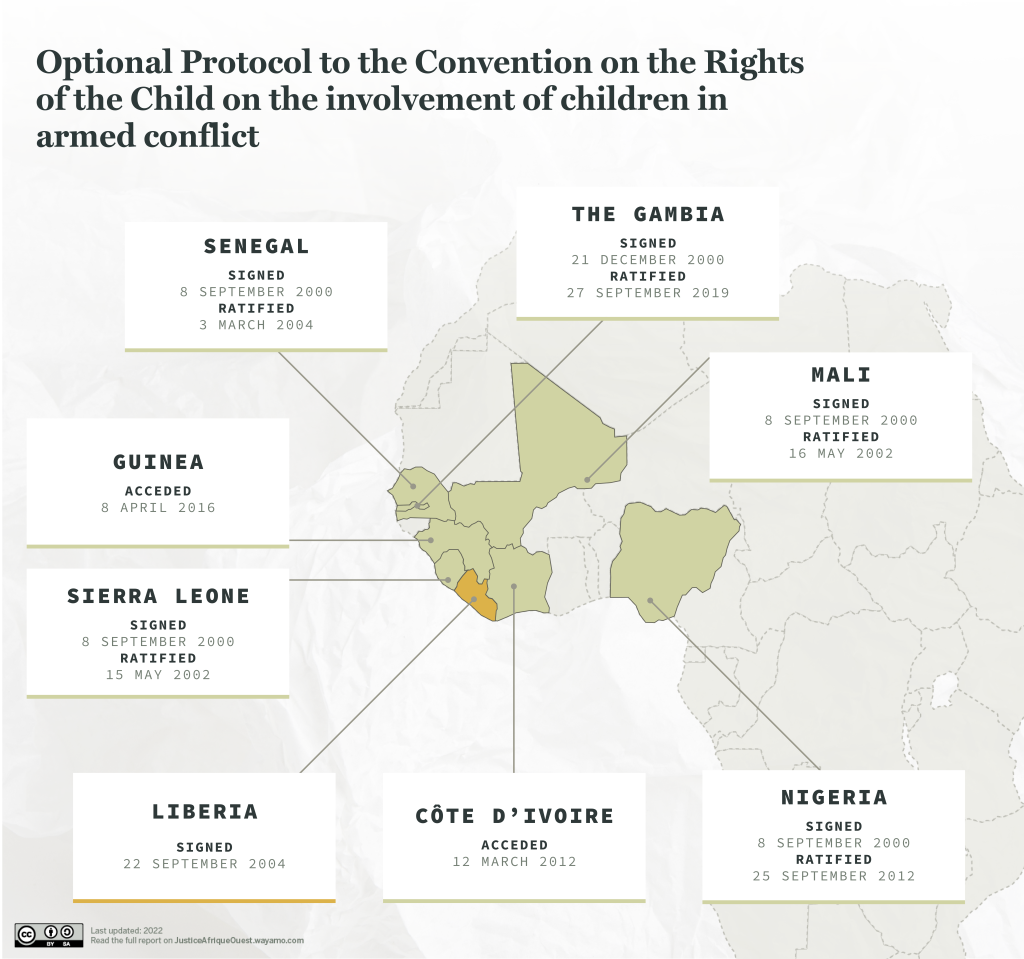

- Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict

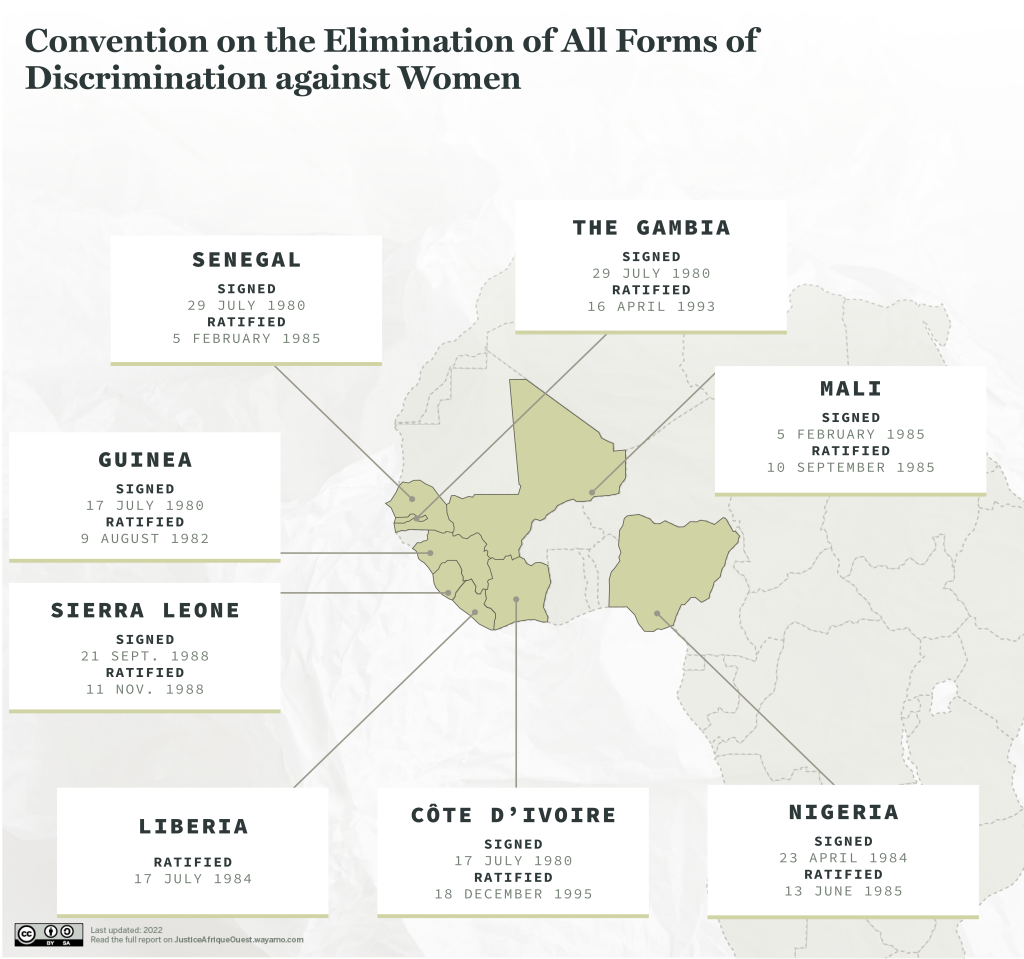

- International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and its Optional Protocol

- Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families

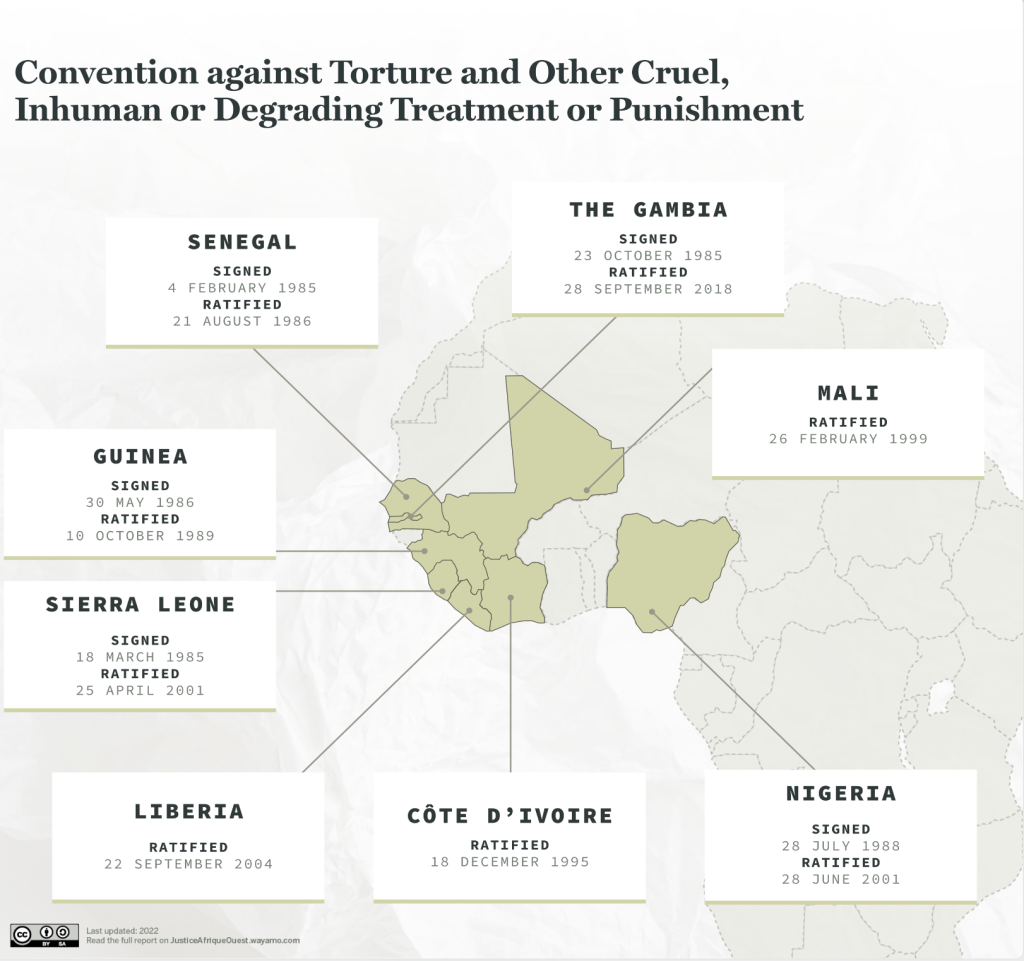

- Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and its Optional Protocol

- Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography

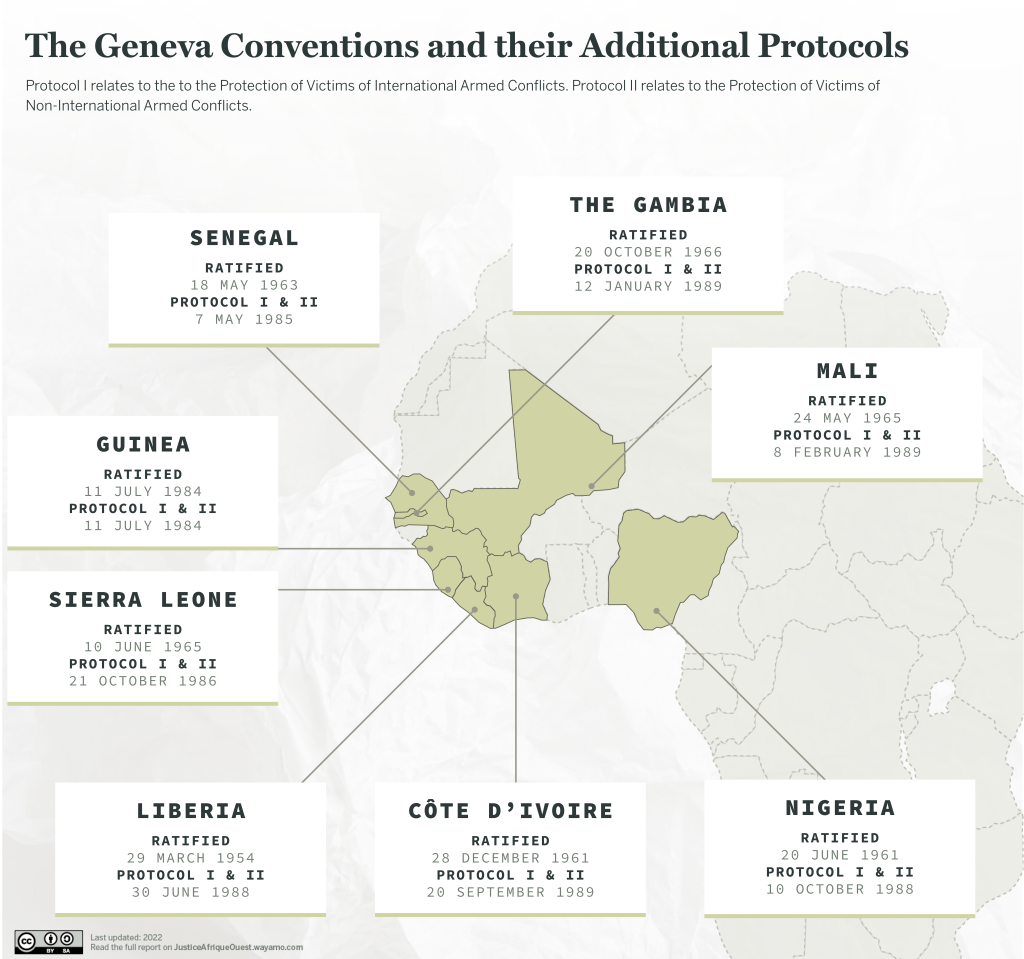

- 1949 Geneva Conventions and their Additional Protocols I and II

- Tehran Resolution on Human Rights in Armed Conflict, 1968

- United Nations Resolution on Human Rights in Armed Conflicts, 1968

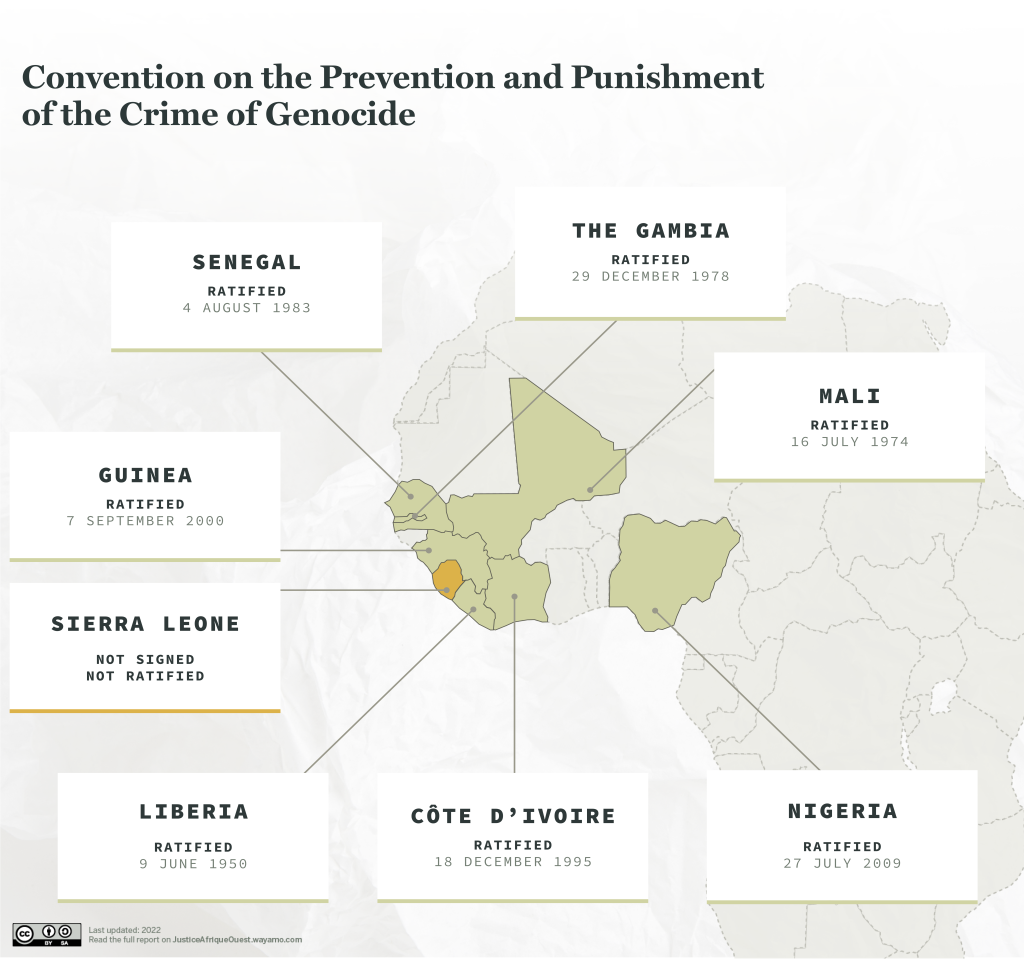

- Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, 1948

- Convention Statutory Limitations to War Crimes, 1968

- 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees and its Protocol

- Conventions of the International Labour Organization (No. 4, 6, 29, 87, 98, 100, 105, 111, 138 and 182)

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and its Optional Protocol

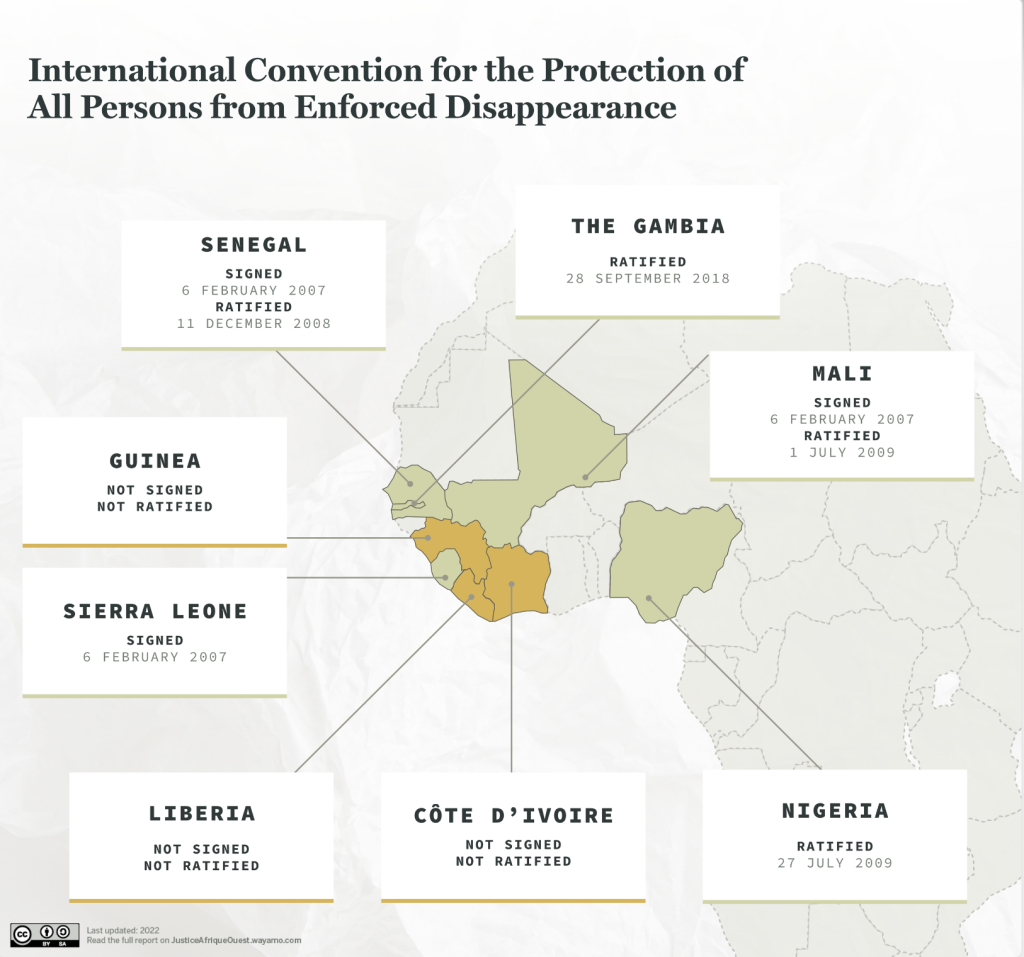

- International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance

- Conventions of UNESCO (note: education, rights to culture and heritage, protection of cultural heritage, such as monuments)

- Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, 1997

- Convention prohibiting Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW), 1980

- CCW amended Article 1, 2001 and CCW Protocol (V) on Explosive Remnants of War, 2003

- Convention on Cluster Munitions, 2008

- Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property, 1954 and Hague Protocol for the Protection of Cultural Property, 1954 and Second Hague Protocol for the Protection of Cultural Property, 1999

- Arms Trade Treaty, 2013

- Convention on Mercenaries, 1989

Priorities and challenges for strengthening domestic accountability in West Africa

Ensuring fair trials

Accountability efforts in West Africa: why should the worst offenders be accorded fair trials?

Effective, credible, and sustainable international criminal justice depends on the fair treatment of those brought before the courts. Every person, including those accused of the most serious crimes, has the right to a fair trial by an independent tribunal. This includes the right to equality before the law, the right to be presumed innocent, and the right to legal assistance, with the latter being free of charge in cases where the accused is unable to pay legal costs. Any defendant, even those accused of the most heinous crimes, deserves the procedural and legal rights afforded by international fair trial standards. Fairness is vital to the credibility and effectiveness of a judicial system. Without it, society will lose trust in the justice system.

The grave nature of international crimes renders fair trials all the more important. The seriousness of these allegations requires fair proceedings and effective representation to prevent a perception of unfair targeting of individuals or of political interference. An unfair trial accepted or intentionally overlooked by the international community would send an unacceptable message to the effect that the human rights of some can be disregarded and that international justice is partial when it comes to those with power or political sway.

Protecting the right to fair trials requires continuous extensive investment in resources and personnel. Fair trials depend on the existence of competent and impartial courts that are shielded from political pressure or interference. Such courts can only be fully effective within the wider judicial system, which includes police and investigators who are trained in and uphold international standards of human rights. They likewise call for prosecutors committed to fairness and concern for the public interest, magistrates who are consistent and impartial in their decisions, and adequate funding and access to the case files for defence counsel. These standards are difficult to maintain in contexts of conflict, where judiciaries must manage a large number of cases, often amidst institutional collapse and political interference.

Resources & Commentary

Jolyon Ford “Bringing fairness to international justice” (Institute for Security Studies: 2009)

This handbook aims to increase understanding of the role of defence counsel in international criminal prosecutions. It is particularly relevant to the African context and is aimed at lawyers from the continent.

Howard Varney et al., Guiding and Protecting Prosecutors (International Center for Transitional Justice: 2019)

This report seeks to assist national prosecutorial organs in developing or strengthening prosecution strategies and guidelines, in order to better align with international standards. The report further offers strategies to help guide prosecutorial decision-making in the wake of violent conflict, where criminal justice systems are weakened and there is a high risk of political interference.

UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and the International Bar Association “Chapter 16: The Administration of Justice During States of Emergency” in Human Rights in the Administration of Justice: A Manual on Human Rights for Judges, Prosecutors and Lawyers (UNHCR: 2003)

This training tool is designed to introduce magistrates to the main legal principles of international human rights law governing the rights and obligations of states during emergency situations. The manual gives detailed legal explanations of the rights which entitle states to derogate from established legal obligations, and presents the conditions which international customary law and treaties impose on States Parties when resorting to emergency measures.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime “Criminal Justice Assessment Toolkit” (UNODC: 2006)

This guide provides practitioners with a ‘toolkit’ for assessing criminal justice systems. It offers guidelines on supporting criminal justice reform and identifying areas of need for technical assistance. The guide further includes tools for assessing the effectiveness of policing, sentencing options, and access to justice measures.

Amnesties

Amnesties for international crimes have been eroded in recent decades due to developing national and international practice and legal opinion. Nonetheless, the issuance of partial and conditional amnesties remains commonplace, particularly as a tool in peace negotiations and the resolution of violent political conflict. No international treaty explicitly prohibits the use of amnesties, including the Rome Statute, though some instruments, such as the Genocide Convention, contain obligations to prosecute perpetrators of genocidal violence.1 While amnesties can be leveraged to protect perpetrators of international crimes, it is also contended that the discretionary use of amnesties may facilitate peace agreements, encourage a repressive regime to step down, or persuade combatants to disarm. Moreover, it is suggested that following bouts of large-scale armed violence, it is not possible for all atrocities and all perpetrators to be addressed or adjudicated.

Critics say that this school of thought seems to favour amnesties over efforts to support national judiciaries’ efforts to handle such war-time criminality. Furthermore, these same critics argue that the use of amnesties for those most responsible for core international crimes would instead perpetuate the concept that accountability can be avoided by the most powerful. While amnesties may be a relevant factor in peace negotiations, the utmost caution is warranted in cases where mass atrocity crimes have been committed. The Statute of the International Criminal Court, for one, does not recognise amnesty of any type as a bar to the prosecution of crimes under its jurisdiction.

In response to atrocities committed during periods of violent conflict or repression, it is typically hoped that states will effectively investigate any atrocities committed, prosecute those responsible and provide remedies to the victims, while also taking effective measures to ensure these crimes will not be repeated in the future. In the immediate aftermath of conflict or repressive rule, it may prove impossible for a state to fulfil this list of duties simultaneously or in a timely manner. This is because these obligations require a transitional government to pursue accountability while also promoting peacebuilding and reconciliation, as well as re-establishing functioning institutions that can address the underlying causes of conflict and effectively prevent future abuses. The latter measures are vital for conflict recovery and prevention, but the steps needed to end violence and promote peace may also undermine or delay accountability.

International law affords states discretionary use of amnesties in these extraordinary circumstances, so long as those amnesties are not unlimited. Limited amnesties would, for example, exclude the gravest offences and offenders, as outlined above. Applicants for amnesty are also often required to meet certain conditions before qualifying, such as surrendering weapons or giving a truthful account of their role in conflict or atrocities. Issuing amnesties in combination with non-judicial or semi-judicial accountability mechanisms, such as truth commissions, further increases the credibility of these measures.

The Rome Statute establishes that traditional immunities for heads of state or senior officials involved in mass atrocities do not apply, but it does not explicitly address the question of amnesties. This leaves open the issue of whether the ICC could defer to an amnesty,2 including those that may be supported by some victims as a means to end a conflict and restore peace. Given this gap in the Rome Statute, it can be argued that the ICC Prosecutor or Chambers may recognise amnesties under certain conditions. In this connection, it has been further argued that the Court may find that an amnesty process would fulfil the ‘complementarity requirement’, thus removing the Court’s jurisdiction based on the criteria that genuine domestic judicial proceedings had addressed the case.3 This, however, seems to be hard to reconcile with the wording of Article 17 of the Rome Statute, which explicitly requires ‘judicial proceedings’, not a political and/or legislative act (which would be the vehicle for an amnesty to be issued). Lastly, the Prosecutor has the authority to decide that, in some exceptional circumstances, it is not in the ‘interests of justice’ to investigate crimes that would otherwise fall within his/her jurisdiction.4 That provision may make for a scenario in which the ICC might defer to amnesties.

Amnesties are not alien to the West Africa context. For example, the 1999 Lomé Peace Agreement between warring parties in Sierra Leone included an amnesty provision for rebel combatants and Foday Sankoh, the leader of the Revolutionary United Front, for any atrocities committed up to the signing of the Agreement. Following a bout of violence after the Agreement was signed, Sankoh was arrested and subsequently surrendered to the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL), a UN-backed hybrid tribunal set up in Freetown. He was charged with seventeen counts of war crimes but died awaiting trial in 2003. The vast majority of rebel forces operating in Sierra Leone have never been prosecuted for their atrocities. Separately, the SCSL judges decided that, while there is a normative trend towards restricting the use of amnesties, this had not crystallised and international law did not prohibit governments from adopting amnesty laws.

Citations & References

1: Transitional Justice Institute Expert Group (2013) “The Belfast Guidelines on Amnesty and Accountability”, Transitional Justice Institute of the University of Ulster.

2: Ronald Slye (2008) “Chapter 7: Immunities and Amnesties” in Max du Plessis ed. “African Guide to International Criminal Justice”, Institute for Security Studies.

3: Ibid.

4: Article 53 of the Rome Statute.

Resources & Commentary

Ronald Slye “Chapter 7: Immunities and Amnesties” in Max du Plessis ed. “African Guide to International Criminal Justice” (Institute for Security Studies: 2008)

This chapter reviews the Rome Statute provisions relating to amnesties and immunities, and explains the conditions under which these measures might be upheld at the ICC.

Jay Butler “Amnesty for Even the Worst Offenders” (Washington University Law Review, 589: 2017)

This article seeks to move away from a binary debate between amnesty and accountability, arguing that this debate is too narrow to respond to the complexity of conflict-resolution demands in many contexts where amnesties are applied.

Transitional Justice Institute Expert Group “The Belfast Guidelines on Amnesty and Accountability” (Transitional Justice Institute of the University of Ulster: 2013)

This resource defines the current legal status of amnesties. Rather than a ‘checklist’ enumerating the elements of an ‘acceptable’ amnesty, these guidelines are a tool for assessing the overall legitimacy of amnesties within a given context.

Political Settlements Research Programme “Amnesties, Conflict and Peace Agreement Database” (University of Edinburgh: 2020)

This database provides annotated, open-access resources on the scope, implementation and effects of amnesties. The resource focuses on amnesties grants during conflict and as part of peace negotiations or peacebuilding efforts.

Outreach

Outreach initiatives promote transparency and inclusiveness, build local ownership, and allow the public to participate and have a voice in justice-seeking

International justice is pursued in the name of the victims, survivors and communities most affected by grave crimes. An outreach strategy is the means whereby these persons can see justice done, and outreach, in turn, is the means whereby truths revealed in the courtroom are shared with the wider society. If trials are to help address the underlying causes of conflict or atrocities, justice institutions must actively engage the public in building a common narrative about the past. Equally, if trials are to contribute to deterring future atrocities, would-be perpetrators must see and understand the consequences of committing grave crimes.

Public engagement should never be an afterthought in judicial proceedings; outreach requires significant investment in planning, personnel and resources. Where successful, those investments yield high returns, both during trial proceedings and in the aftermath. Communities that have long awaited justice have understandably high, and at times unrealistic, expectations of prosecutions or reparations measures. Outreach is essential for ensuring that transparent and accurate information is available to victims’ communities. These initiatives also provide a means for those communities to dialogue with judicial institutions about their concerns and needs.

If the public feels that a trial is credible and legitimate, it will begin regaining trust in judicial institutions and be more likely to cooperate with official judicial proceedings. Outreach programmes are also essential for defusing misinformation that powerful persons accused of grave crimes might spread to supporters about their trial process. Without an effective means of communication to the public, misinformation can sow panic amongst ex-combatants, who may refuse to cooperate or even threaten a return to arms.

Resources & Commentary

Clara Ramírez-Barat, “Making an Impact: Guidelines on Designing and Implementing Outreach Programs” (ICTJ: 2011)

This report examines outreach initiatives from a variety of contexts, including the Sierra Leone Special Court, International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. It provides practitioners with practical guidance on designing and implementing outreach programmes.

Norma Henry Prentelovitch “Seeing Justice Done: the Importance of Prioritizing Outreach Efforts at International Criminal Tribunals” (Georgetown Journal of International Law 39: 2008)

This article argues that outreach is essential to the mission of international tribunals. Without efforts to engage victims and communicate reliable information about proceedings, perpetrators may become the focus of justice efforts, leaving victims feeling left behind.

Implementing domestic legislation to prosecute international crimes

To the extent possible within a country’s judicial system and political climate, many assert that states have a duty to hold the most serious violators of human rights and international law to account in domestic courts. The individual state’s responsibility for prosecuting international crimes is defined in a number of international treaties, and as such is clearly reflected in Article 17 of the Rome Statute.5 As part of its treaty commitments, each State Party to the Statute agrees to enact ‘implementing legislation’ that allows domestic courts to hold persons accused of international crimes to account. Yet, the core challenge of enacting “implementing legislation” is ensuring that crimes defined in the Rome Statute are also codified as crimes in domestic law.

In meeting this requirement, a state must determine the extent to which existing domestic laws can be applied to prosecute international crimes, and identify discrepancies requiring amendment or new legislation.

Some legal systems permit the direct application of international customary law and treaties in national courts. In contexts where treaties are directly applicable, international crimes enter the domestic legislature through ratification of the Rome Statute and other core treaties defining international criminal law, international humanitarian law, and human rights law (e.g., the Geneva Conventions and its Protocols, Genocide Convention, Hague Convention of 1907, and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights). Yet only some states follow this doctrine of direct applicability of international treaties in national law. Many legal systems require that treaties are domesticated through drafting and passing national laws codifying the terms of the treaty into domestic legislation.

Independent of the vehicle chosen by a state to make international law directly applicable in a national context, most national legal systems include elements of international crimes in their domestic criminal law. Constitutional prohibitions on human rights violations and national laws codifying ‘ordinary’ crimes such as murder, torture and sexual violence are but some examples. In some contexts, these laws may sufficiently reflect the crimes defined in the Rome Statute to meet the standard required for effective ‘complementarity’ between national courts and the ICC. In other contexts, amendments or additions will be necessary to address gaps in domestic legislation, where international legal texts do not apply directly in domestic law.

Even in contexts where international crimes have been incorporated into the national legislation, barriers may still remain to holding perpetrators of international crimes to account in domestic courts. This could be the case where national legislation precludes accused perpetrators from prosecution due to amnesties or official immunities. Another example could be where the domestic criminal code does not include command responsibility as possible form of criminal liability (though in most cases liability can be construed through domestic rules on criminal liability by omission).

Many national justice systems apply a strict understanding of the principle that no-one can be retroactively charged for a crime that was not codified in national legislation at the time the offence was committed. This can have implications for efforts to hold perpetrators of international crimes accountable in domestic courts. Newly ratified treaties or newly drafted laws that bring international crimes into national legislation may come too late to be applied to crimes committed in the years or decades before the ratification of such treaties. In such cases, legal systems can allow the direct application of international law as a legal avenue for the domestic prosecution of international crimes which provides that an act considered illegal under international law cannot be barred from prosecution due to lack of codification in the relevant national context. Another way to achieve accountability retroactively, albeit through ICC involvement, could be retrospective application of the Rome Statute (by virtue of Article 12(3) of the Rome Statute) as far back as July 2002.6

One aspect that may foster domestic accountability for international crimes is the cooperation regime between states and the ICC, as envisaged in Part 9 of the Rome Statute.7 It has to be said though that such cooperation will prove beneficial for national investigations/prosecutions at the operational level; when it comes to the enacting legislation, it will be other States Parties to the Rome Statute which may assist states in need with model legislation and their own experience with national legislative implementation texts. This is where inter-state cooperation under the Rome Statute umbrella may prove instrumental in enabling domestic judiciaries being provided with the tools they need to achieve seamless accountability for the worst crimes.

Citations & References

5: Article 17 of the Rome Statute.

6: Article 12(3) of the Rome Statute.

7: See the ICC’s state cooperation regime in Part 9 of the Rome Statute.

Resources & Commentary

Amnesty International “International Criminal Court: Updated Checklist for Effective Implementation” (Amnesty International: May 2010) (FR)

This checklist offers recommendations for assessing a state’s legislation and judiciary, to ensure that the ICC is an effective complement to national courts and legally prepared to cooperate with the Court.

Universal jurisdiction

The principle of universal jurisdiction extends from the claim that certain crimes are so grave — crimes against humanity, genocide, war crimes, aggression, torture and the like — as to be considered offences against the whole human community. By this logic, the universally egregious nature of the harm done imposes a duty on all states to prosecute those responsible, with the universally felt nature of that harm serving as a source of judicial authority shared by all states to prosecute the perpetrators. Incorporating universal jurisdiction into national law enables a state to exercise jurisdiction over persons accused of certain especially egregious crimes, regardless of where the crimes were committed and the nationality of the accused and/or victims. Yet, applying immunities to some perpetrators may hinder prosecutions by other national authorities; in these cases, only an international criminal tribunal can overcome such immunities.8

Play Video

Justice for Victims in Liberia: Application of the Principle of Universal Jurisdiction

Alain Werner, Director of Civitas Maxima, looks back at the trials that took place in France, Switzerland and the United States for war crimes committed in Liberia. In this interview, Werner presents the work of Civitas Maxima as well as the different judicial mechanisms that were implemented to bring justice to the victims. Werner underlines the importance of these initiatives and hopes to one day see justice done on Liberian territory.

Citations & References

8: See International Court of Justice, Arrest Warrant of 11 April 2000 (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Belgium), 2000.

Resources & Commentary

Trial International Universal Jurisdiction Annual Review 2020 — Terrorism and international crimes: prosecuting atrocities for what they are (Trial International: 2020)

This Since 2014, Trial International has collected comprehensive data on ongoing investigations and trials that fall under universal jurisdiction. Their 2019 research reveals a 40% increase in the number of global universal jurisdiction cases since the previous year. This included 16 convictions in 16 different prosecuting countries, as well as 146 charges of crimes against humanity, 21 charges of genocide and 141 charges of war crimes.

.